For nothing passes, without re-creation …

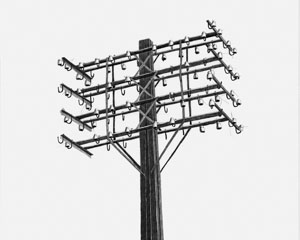

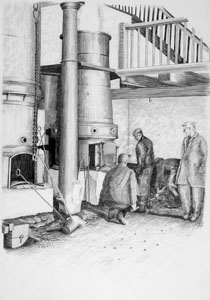

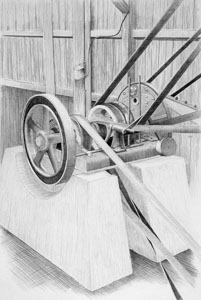

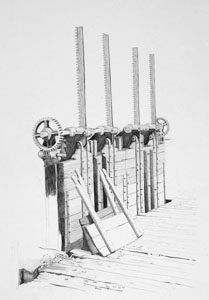

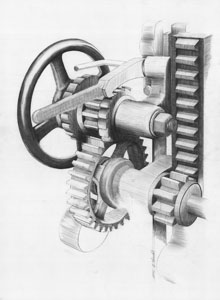

You need to have an eye for that “something special” in everyday life. If a high rise storage warehouse is built, then the layman marvels at the impenetrable tangle of rods, poles and fittings. If countless empty cable drums are stacked up in a work yard, they are seen and forgotten a moment later by a passerby. After all this is what work yards are for. And whoever visits an old windmill or carpentry workshop will be fascinated with the old engineering, see gearwheels and drive belts that set millstones or saws in motion, and have nostalgic childhood memories of the good old days, when craftsmanship was still a combination of muscle and machine power.

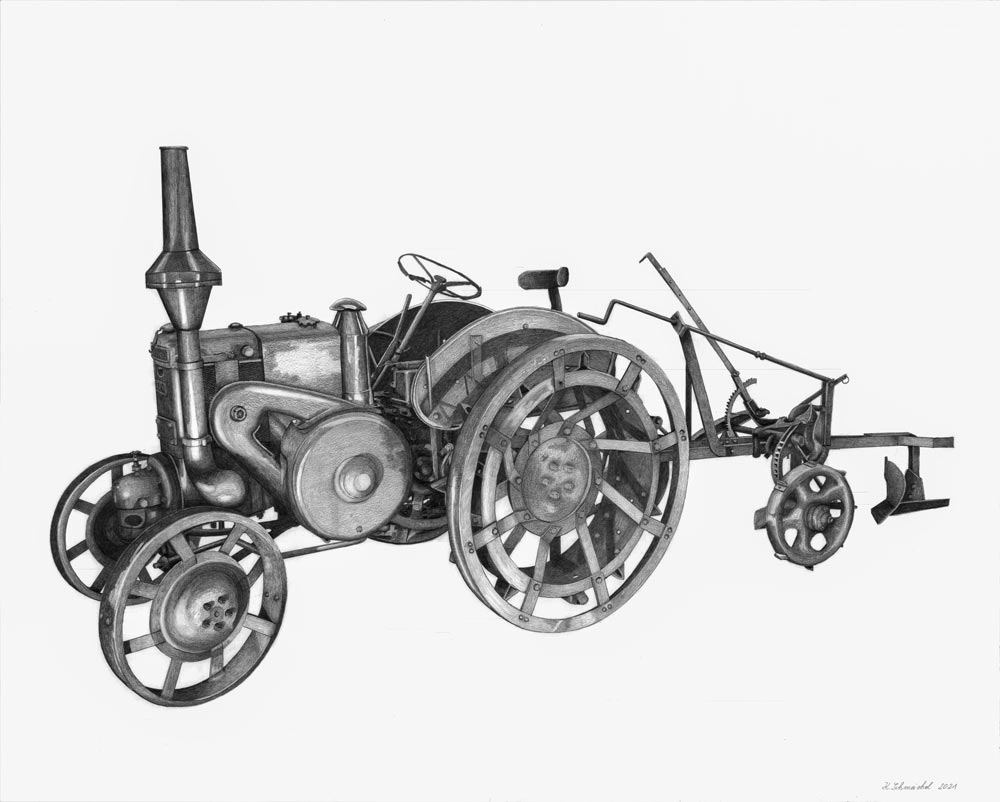

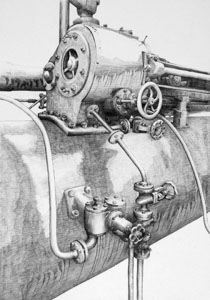

But one can also view such construction sites, warehouses and workshops like Karl Schmeichel. He looks at patterns and sequences, at spatial structures and the shapeliness of wheels, pumps, pipes and flanges covered in nuts and bolts, connecting components. Whether wood, iron, steel or concrete – the material is not important to Schmeichel. It just needs to have aesthetics.

complete text by Peter Groth

The object is photographed from different perspectives. These photos then serve Schmeichel as a model for his drawings that play a special role in his work, although not his only means of artistic expression. In his graphic work he is not concerned in the exact interpretation of a photograph into a drawing – he is interested in the technical object, its form, surface, light and shade, the structure.

As in the case of the drawings for example, whose photographic models were of an under construction high rise storage warehouse with-out the exterior shell. Karl Schmeichel uses a pencil to draw, in exact detail, the structure of the poles, paying attention to the perspective of this tangle of steel and so achieves a remarkable depth effect. The eye can get lost in these leaves, following the lines and only suspects the later function.

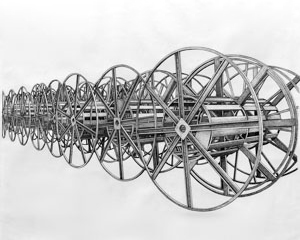

However it does not always have to be such a huge object that attracts the artist. By chance he found several empty man sized cable drums in the storage area of a civil engineering company, standing there in rank and file. Always the same size and form, the same type – Schmeichel was fascinated. He was inspired by his discovery to make a pencil drawing, in which he accurately reproduces the lined up drums. On the completed sheet the drums with their characteristic curves and welded cross braces are enormously compressed, forming an apparently almost unravelable large ball – and yet they are only the sequence of a repetitive object.

But Karl Schmeichel can produce smaller and more detailed work if he finds individual gearwheels, drive belts, bolts, screws and pumps as models in industrial companies and craft workshops. Here too it is lines, shades and structures within the small objects that animate him. If he visits a farmer’s cartwright or blacksmiths it is also the transience of the craft that inspires him to realistically depict the individual tools.

The draftsman’s delight in reproducing technical structures and devices is no coincidence – Schmeichel has an apprenticeship as a machine fitter. He later worked in the construction of machines for the pharmaceutical industry, requiring precision to a tenth of a milimeter. After further school education and an excursion of several years into furniture making, Schmeichel studied at the Staatliche Werkakademie fuer Gestaltung in Kassel, which he completed in 1994.

He already began his artistic activity in 1992, not limiting himself to drawing. He created sculptures from wood and concrete, built furn-iture that appear to be a hybrid between utility objects and art, and tried his hand at the technique of pen and ink drawing, which meant a step towards free interpretation sketches. And so the feather landscape representations were created, which, in turn were influenced by artistic elements of the line and the now amorphous structures are alive, but reserved in terms of colour. The silhouette of a forest edge with its high, straight tree trunks, a heap of harvested sugar beet or simply the structure of a not yet cultivated field are all motives which lead Karl Schmeichel on new artistic paths.

Handcrafted these sheets are also of the highest accuracy and characterised by the surety in association with composition and format.

A chance discovery has led Karl Schmeichel into another artistic genre, in the processing of rust objects. He discovered that thin sheets of metal which had been stored for several years, had rust in varying shades of colour and had even begun to disintegrate. The “ageing” iron with its eroded holes and irregular edges, with partly still existent original colours and rust tones so typical for the decaying process, were cleaned by Schmeichel, sprinkled with sand and covered with vegetable colours and egg tempera. So he created a new colour impression, underlined by the use of mineral sand, the crannied, haptic surfaces of almost mansized objects, thus creating material images of great optical appeal. The decaying process is not halted with the artistic treatment, at the best influenced by the use of sand and paint. The disintegration continues. Karl Schmeichel doesn‘t mind. As he says “ Nothing passes, without re-creation”.

The artist is working at it, you only need to have a special eye to see the speciality in everyday life.

Peter Groth